In this post in our mini-series on sustainability in the outdoor apparel industry we start to have a look at some of the brands which do better than others when it comes to sustainability. The problem with deciding which brands are the most sustainable lies both in scale and transparency. In terms of scale, it is hard to decide what matters most – a small company which does a lot, but with limited reach or a huge company which only makes a limited effort, but with a bigger impact all-over due to production and sales volume.

Transparency is, however, the biggest problem when it comes to sustainability. In the past years the term ‘greenwashing’ has been used more and more often for companies which advertise far and wide about how sustainable or ‘natural’ their products are, but have problems walking the talk in reality. As companies are not obliged to divulge just how sustainable their production and products are, it can be hard to detect what is real or just marketing spin. Truly sustainable brands will therefore often offer very concrete numbers on how they are doing in terms of optimizing their production to the benefit of the environment, animals and humans involved.

The outdoor brands we have chosen for this list display relatively great transparency, whether in the form of concrete numbers on their website or in yearly reports. One thing is for sure: Sustainability does not come cheap or easy – it takes time and resources to change the structures needed to design, produce and sell just about any product in a sustainable manner. To be certain that a brand really walks the talk, it is good if it is certified by outside set standards, such as:

- Bluesign for the entire production process of all types of textiles.

- Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) for all natural fabric materials (i.e. not synthetics).

- Responsible Down Standard (RDS) or Global Traceable Down Standard for down-insulated products.

- OEKO-TEX Standard 100 to certify the absence of harmful chemical substances in textiles.

- Responsible Wool Standard (RWS) for products containing wool.

- Leather Working Group (LWG) standard for leather, suede and nubuck product or parts.

The brands on this list of sustainable outdoor brands all have products which are certified by such standards to a very high degree. It is very important to cooperate with and be certified by independent outside partners because it means that a company’s actions and initiatives are scrutinized by others than itself.

Sustainable outdoor brands:

Patagonia

Let’s start with the obvious brand for this list – Patagonia. The awareness of the company’s sustainability policy really skyrocketed in 2011 when Patagonia ran the legendary “Don’t buy this jacket” campaign, encouraging people to do just about anything else (repair, reuse, recycle etc.) before buying a new garment. Over the years Patagonia has launched a varied range of initiatives to make more sustainable apparel and gear (see more in the list below), but the company has also been challenged by NGOs criticizing how it has approached the goal of sustainability – for example Greenpeace with regards to PFC-treated shell layers, and PETA and other animal-right groups with regards to the use of down and wool. Nevertheless, Patagonia is generally considered as one of the most sustainable outdoor brands around.

Patagonia initiatives:

- Patagonia was the first outdoor brand to fully implement organic cotton in the late 1990’s.

- As of fall 2018, all wool in Patagonia products is RWS certified, from farm to finished product.

- In 2014 all virgin down adhered to the brand’s Traceable Down Standard (a rival to the more common RDS standard); in 2017 it also became certified by the Global Traceable Down Standard.

- The brand goes new ways when it comes to recycled fibers, for example in regards to recycled cashmere and wool (see more in video below). More conventional recycled fibers include nylon, polyester, cotton and also down.

- Patagonia has launched the Guppy Friend washing bag in an effort to decrease micro plastic pollution from synthetic materials.

- Like online retailer REI, Patagonia sells inspected and repaired apparel and gear under the name Worn Wear – but only the brand’s own products.

Issues:

- From Patagonia’s website it is not clear how much (or little) a sustainable option is utilized over the conventional, for example with regards to the use of recycled materials over newly sourced.

Shop Patagonia at Patagonia –>

Video about recycling wool for Patagonia

Vaude

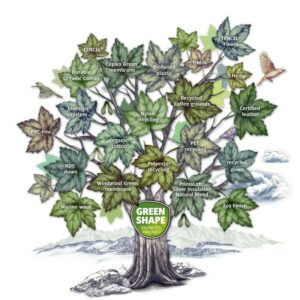

German Vaude is another frontrunner when it comes to sustainability in the outdoor apparel and gear industry. The family-owned company was established in 1974 and does very well in terms of transparency as it for the past many years has released a yearly sustainability report (typically published in the summer time the following year) where Vaude divulges both the good and the not-so-good. Vaude puts emphasis both on fair pay throughout the entire supply chain (as an affiliate of the FairWear Foundation and an environmentally sustainable production. The brand has made its own sustainability standard called the Green Shape, which 98% of its Summer 2019 apparel collection adhered to.

Vaude Green Shape Characteristics:

- Designed to be durable and repairable.

- RDS-certified down insulation in both jackets and sleeping bags.

- Wool fibers comes from RWS-certified Merino wool.

- Leather products or parts are Gold-rated by the LWS standard and sourced in Northern Germany.

- Cotton fibers are 100% organic (GOTS-certified) except those in the brand’s caps and jeans (which are mixed with PrimaLoft and conventional cotton).

- Completely PVC-free products from summer 2019 onwards.

- Cooperation with bluesign since 2001 resulting in a high percentage of bluesign-certified materials in every collection.

- Use of various recycled materials, both synthetic (plastic) and natural (hemp, down etc.).

Issues

- The yearly sustainability/CSR report fails to answer a few standard questions by the goodonyou website.

- While the yearly CSR report is substantial and impressive, it can be hard to navigate in the abundance of information and details.

Video about Vaude Green Shape Eco products

Klattermusen

Klattermusen is a Swedish outdoor apparel and backpack company, which already from the inception in 1975 focused on its designs having a long life-span, and still offer spare parts and repairs for the products. Today, it is nevertheless most impressing how dedicated Klattermusen is to sustainable materials for all of its designs. It switched to 100% organic cotton in 2006, has been a bluesign partner since 2007, was the first outdoor company to completely remove PFOA (one of the most hazardous fluorocarbons) from all garments already in 2008, introduced nylon from recycled fishing nets in 2009 in all backpacks, and was the first outdoor brand to achieve a 100% fluorocarbon-free collection in fall 2017. Klattermusen also partners with RePack which is a reusable packaging service.

Klattermusen’s Sustainable Fabrics Policy:

- All cotton fibers are 100 % organic

- Bluesign-approved Kevlar and Wind Stretch fabrics

- DWR-treatments 100% free of fluorocarbons.

- Merino wool is chlorine-free and sourced from sheep which have not been exposed to mulesing.

- Only RDS-certified down.

- The utilized polyamide is mainly bean-based or recycled rather than fossil fuel-dependent.

- PFC-free fabrics (except a few zippers as the brand has not yet found a PFC-free alternative).

Issues:

- Not always transparent how much (or little) a sustainable option is utilized over the conventional, for example with regards to Klattermusen’s use of recycled polyester.

- No comments on fair wages for textile workers, but as most of Klattermusen’s products are made in the quite well-regulated EU, it is a smaller concern.

Shop Klattermusen on Amazon –>

Shop Klattermusen on Moosejaw –>

Jack Wolfskin

2017 launch of Jack Wolfskin Texapore Ecosphere as reported on by Digitaltrends.com

While the company name might sound slightly corny, German outdoor brand Jack Wolfskin has been deemed nothing less than a ‘Leader’ by the Fair Wear Organisation in the latest performance check report, for instance by monitoring 100% of its supply chain. The brand, however, also focuses on environmental impact of its production and has the goal that all fabrics and 75% of various components (such as buttons, zips, drawcords, etc.) are from bluesign-certified manufacturers from 2020 onwards. Already in summer 2016 two-thirds of the fabrics used in the apparel collection were bluesign-approved. In 2012 it was decided to eliminate all PFCs from Jack Wolfskin products by 2020, and progress has been made year by year – 89 % of the clothing in the 2017 summer collection was PFC-free. The same year the brand launched the Jack Wolfskin TexaPore Ecosphere jacket which is entirely made of recycled materials (see more in video below).

Sustainability Actions:

- Jack Wolfskin has made a GreenBook (based on various global requirements such bluesign and OEKO-TEX) about harmful substances that all the brand’s suppliers and manufacturers must comply with.

- Only 100% organic cotton since summer 2013.

- Down insulation is exclusively sourced from RDS-certified production sites from fall 2017.

- Since 2012, 100% of Jack Wolfskin’s suppliers are regularly audited by independent auditors. The Fair Wear Foundation carries out the verification audits.

- PVC-free products since 2012.

- Ban on nanotechnology since 2010 due to the uncertainty of its impact on human health.

Issues:

- Certain published reports on the website are a few years old, such as the Environmental Report and the Social Report.

- Very non-committing statements on the website, for example in relation to wool from sheep which have been exposed to mulesing: “Jack Wolfskin wants to distance itself from this practice and uses certification to ensure that all of its Merino wool is obtained without the use of mulesing. 12/2010 – No proven use of mulesing for Jack Wolfskin products”. Which kind of certification are we talking about?

Shop Jack Wolfskin on Amazon –>

Shop Jack Wolfskin on Moosejaw –>

Video about Jack Wolfskin Texapore Ecosphere

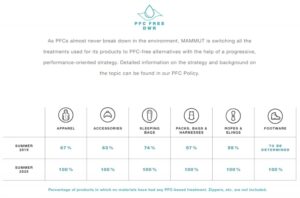

Mammut

Swiss outdoor brand Mammut (dating back to 1862) has the sustainability motto “We CARE”. C stands for Clean production, A for Animal welfare, R for Reduced footprint and E for Ethical production. Other companies could really learn something from Mammut’s generally easy-to-read infographics under each area, revealing how much a given category of their 2019 line (divided into Accessories, Apparel, Footwear, Ropes & Slings, Sleeping Bags, and Packs, Backs & Harnesses) adheres by percentage to a given standard (bluesign, RDS etc.). A 2025 target for each standard under each product category is also specified. A complete Target Report for 2025 can also be downloaded. The numbers in the report, however, also reveal that Mammut is still on a journey towards sustainability – as the other brands on this list – but with relatively high goals for the years to come. In 2019 the company became a member of the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC) and has begun the implementation of the so-called HIGG index in an effort to be able to measure and compare the impact of the brand’s corporate responsibility initiatives. In terms of fair trade, Mammut is already a member of the Fair Wear Foundation, which focuses on workers’ conditions in the supply chain after fabric production, and publishes the FWF’s objective report on the brand’s performance.

Mammut’s Sustainable Fabrics Policy:

- All down products use either RDS-certified or recycled down sourced through RE:Down.

- All of Mammut’s leather suppliers have a LWS rating of Silver or higher.

- For all product categories except Footwear (still ‘to be determined’), between 55% – 74% of the products contained no materials with a PFC-based treatment. The 2025 target is 100% across the board.

- The 2025 target for the percentage of bluesign-approved fabrics is 95% for both apparel, sleeping bags and backpacks, but the respective 2019 values are only 65%, 68% and 30%.

- The 2025 target for apparel containing at least 70% cotton is that 100 % of it is organic, but the current 2019 percentage is only 30%.

Issues:

- There are a few infographics where the 2019 certification rate is missing – for example the use of certified leather for accessories and footwear, Merino wool for apparel or the absence of PFC-based treatments on footwear.

- Not all infographics on the website/target report are equally comprehensible. For example the ‘explanation’ for the infographic relating to the use of recycled materials: “Percentage of materials used that are at least 75% polyester where at least half of the polyester fiber is recycled”.

You forgot Houdini Sportsware, https://houdinisportswear.com/en-gl – one of the best there is. 🙂